-

- PCB TYPE

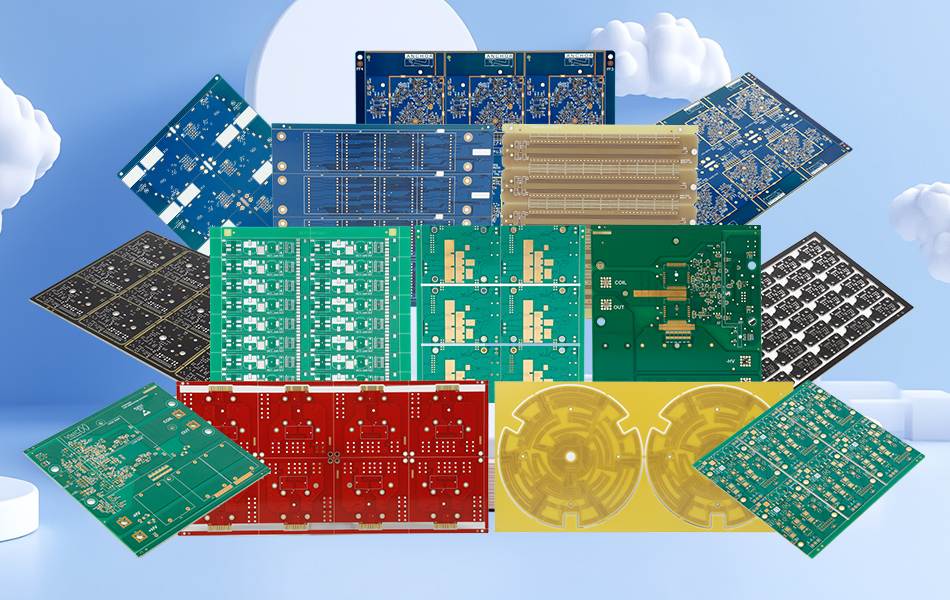

- PRINTED CIRCUIT BOARD PROTOTYPE ALUMINUM PRINTED CIRCUIT BOARD R&F PCB FPC HIGH FREQUENCY PCB HIGH-TG PCB HEAVY COPPER PCB HDI PCB PCB FOR LIGHTING METAL CORE PCB

time:Aug 07. 2025, 17:40:55

In the realm of printed circuit board (PCB) design, thermal conductivity is a parameter that directly impacts reliability, especially as electronic devices grow smaller and more power-dense. Among the most widely used PCB materials, FR4 stands out for its versatility, and a key metric defining its thermal performance is a thermal conductivity of approximately 0.3W/mK. This value—0.3 watts per meter-kelvin—represents FR4’s ability to conduct heat, a critical factor in dissipating thermal energy from components like microprocessors, LEDs, and power transistors. While 0.3W/mK may seem modest compared to metals (e.g., copper at ~401W/mK) or specialized ceramics (e.g., aluminum oxide at ~30W/mK), it strikes a unique balance between cost, manufacturability, and thermal management for the majority of electronic applications. This article explores the significance of FR4 PCB thermal conductivity at 0.3W/mK, its underlying material science, practical implications for design, and strategies to optimize heat dissipation within this constraint.

Thermal conductivity (k) measures a material’s ability to transfer heat through conduction, with higher values indicating more efficient heat flow. For FR4 PCB, the typical thermal conductivity of 0.3W/mK is a product of its composite structure: a matrix of epoxy resin (low thermal conductivity, ~0.1–0.2W/mK) reinforced with E-glass fibers (moderate thermal conductivity, ~1.0–1.2W/mK). This combination results in an effective thermal conductivity that is greater than pure epoxy but lower than glass alone, reflecting the heterogeneous nature of the material.

To contextualize 0.3W/mK: it means that, under steady-state conditions, 0.3 joules of heat will flow per second through a 1-square-meter cross-section of FR4 when there is a 1-kelvin temperature difference between the two ends. In practical terms, this translates to FR4’s ability to dissipate heat from a hot component (e.g., a 1W LED) over short distances (millimeters) without excessive temperature buildup—sufficient for low-to-moderate power applications. However, for high-power devices (e.g., 10W+ power amplifiers), this conductivity becomes a limiting factor, requiring designers to implement supplemental cooling strategies.

The 0.3W/mK thermal conductivity of FR4 PCB is not arbitrary; it is determined by the interplay of its constituent materials and manufacturing processes:

Epoxy Resin Matrix: The primary binder in FR4, epoxy resin has inherently low thermal conductivity due to its amorphous molecular structure, which limits phonon (heat-carrying particle) propagation. Standard bisphenol-A epoxy resins, used in most FR4 formulations, contribute minimally to heat transfer, with conductivity values as low as 0.15W/mK. This low conductivity is the primary reason FR4’s overall k remains modest.

E-Glass Fiber Reinforcement: Woven E-glass fibers enhance mechanical strength but have a more significant impact on thermal conductivity than epoxy. With a conductivity of ~1.1W/mK, glass fibers act as limited "heat highways" within the laminate. However, their woven structure—with gaps filled by epoxy—creates thermal barriers, preventing continuous heat flow. Thicker weaves (e.g., 7628) increase glass content (up to ~60% by weight) but only marginally boost thermal conductivity to ~0.35W/mK, as epoxy still dominates the matrix.

Fillers and Additives: Some FR4 variants include inorganic fillers (e.g., silica, aluminum oxide) to reduce thermal expansion or improve mechanical properties. While these fillers have higher thermal conductivity than epoxy (silica at ~1.4W/mK, alumina at ~30W/mK), they are typically added in low concentrations (10–20% by weight) to avoid brittleness. This limits their ability to enhance overall thermal conductivity, with filler-modified FR4 achieving at most 0.35–0.4W/mK.

Manufacturing Processes: Lamination pressure and temperature influence the density of the FR4 matrix. Higher pressure (300–400 psi) reduces voids between resin and fibers, creating more continuous thermal pathways. However, even optimized lamination cannot overcome the fundamental limits of the epoxy-glass combination, keeping conductivity near 0.3W/mK for standard grades.

FR4 PCB’s 0.3W/mK thermal conductivity is well-suited for many applications but becomes a constraint in high-power scenarios. Understanding these boundaries is key to effective design:

Suitable Applications: For low-to-moderate power devices (≤5W), 0.3W/mK is sufficient. Examples include:

Consumer electronics: Smartphones, tablets, and wearables, where components like application processors (1–3W) generate localized heat that dissipates through the PCB to the device chassis.

LED lighting: Low-power LEDs (≤3W) in residential fixtures, where heat spreads from the LED pad through the FR4 PCB to a small heat sink.

Sensors and IoT devices: Low-power microcontrollers (≤1W) in environmental sensors, where ambient airflow complements FR4’s conduction to prevent overheating.

Challenging Applications: For high-power components (>5W), 0.3W/mK often requires supplemental cooling:

Power electronics: Motor drives, inverters, and DC-DC converters with power MOSFETs or IGBTs (10–50W) generate significant heat that FR4 cannot dissipate quickly enough, leading to hotspots.

High-performance computing: GPUs or FPGAs in servers (20–100W) require active cooling (fans, liquid cooling) to complement FR4’s conduction.

Automotive underhood systems: Engine control units (ECUs) with power management ICs (5–15W) operate in high ambient temperatures, amplifying the need for enhanced thermal management.

While FR4’s 0.3W/mK conductivity is fixed, designers can implement strategies to maximize heat flow within this constraint:

Thermal Vias: Placing arrays of plated through-holes (vias) beneath hot components creates vertical thermal pathways from the component pad to internal or bottom-layer copper planes. These vias, often filled with conductive epoxy, reduce thermal resistance by 30–50% compared to solid FR4, allowing heat to spread across larger copper areas. For a 3W LED, a 4x4 array of 0.3mm vias can lower component temperature by 10–15°C.

Increased Copper Weight: Thicker copper (2–4 oz vs. standard 1 oz) on power and ground planes enhances lateral heat spreading. Copper’s high thermal conductivity (~401W/mK) allows it to distribute heat across the PCB surface, reducing localized hotspots. A 2 oz copper plane can dissipate 20–30% more heat than a 1 oz plane of the same area.

Component Placement: Locating hot components near PCB edges or cutouts allows heat to escape to the surrounding environment via convection. Separating high-power devices (e.g., a 5W regulator and a 3W transceiver) by 10–15mm prevents cumulative heating, leveraging FR4’s 0.3W/mK conductivity to limit cross-talk between hot zones.

Copper Pour and Plane Design: Using large, continuous ground or power planes (instead of isolated traces) provides a low-resistance thermal path. These planes act as "heat spreaders," distributing energy from hot components across the PCB. For example, a 50mm x 50mm copper plane on a 0.3W/mK FR4 PCB can dissipate 2–3W of heat with a temperature rise of <20°C above ambient.

Conformal Coating and Heat Sinks: For outdoor or dusty environments, a thin layer of thermally conductive conformal coating (e.g., silicone with aluminum oxide fillers, ~1.0W/mK) protects the PCB while slightly enhancing heat transfer. For higher power, attaching a low-profile heat sink to the component or copper plane—using thermal interface material (TIM) to fill air gaps—can reduce temperatures by 20–40°C, complementing FR4’s conduction with conduction and convection through the heat sink.

Accurately measuring how 0.3W/mK FR4 PCB performs in real-world conditions is critical to ensuring reliability. Key testing methods include:

Thermal Imaging: Infrared (IR) cameras capture temperature distributions across the PCB, identifying hotspots and verifying the effectiveness of thermal vias or copper planes. For a 5W power module on FR4, IR imaging might reveal a 30°C hotspot at the component, which drops to 15°C with a 4x4 via array—confirming improved heat spreading.

Thermal Resistance Measurement: Using a thermal test die (a calibrated heater/sensor) to measure the thermal resistance (Rθ) from the component to ambient. For FR4 PCB, Rθ typically ranges from 20–40°C/W for a 1cm² copper pad, meaning a 2W component would experience a 40–80°C rise above ambient—data that guides cooling design.

Finite Element Analysis (FEA): Simulation tools (e.g., ANSYS, COMSOL) model heat flow in 0.3W/mK FR4, predicting temperatures for different component layouts and cooling strategies. FEA allows designers to optimize via placement or copper plane size before prototyping, reducing development time.

Operational Testing: Subjecting the PCB to typical operating conditions (e.g., 85°C ambient, full load) and monitoring component temperatures with thermocouples. This validates that FR4’s 0.3W/mK conductivity, combined with design optimizations, keeps components within their safe operating temperature range (e.g., <125°C for most semiconductors).

While 0.3W/mK FR4 is cost-effective, some applications require higher thermal conductivity. Comparing it to alternatives highlights tradeoffs:

Thermally Enhanced FR4: Modified with ceramic fillers (e.g., aluminum oxide, boron nitride), these variants achieve 0.5–0.8W/mK. They cost 20–30% more than standard FR4 but offer better heat dissipation for 5–10W components, making them ideal for industrial sensors or mid-power LED drivers.

Metal-Core PCBs (MCPCBs): Using an aluminum or copper core (1–2W/mK), MCPCBs offer 3–10x higher thermal conductivity than FR4. They excel for high-power LEDs (10–50W) but cost 2–3x more than FR4 and are less flexible for complex, multi-layer designs.

Ceramic Substrates (Alumina, Aluminum Nitride): With conductivity up to 200W/mK, ceramics are superior for ultra-high-power applications (50W+). However, they are brittle, expensive (10–20x FR4), and limited to simple, low-layer designs—overkill for most consumer or industrial electronics.

Copper-Clad Invar: Invar (a nickel-iron alloy) has low thermal expansion, and when clad with copper, offers ~10W/mK conductivity. Used in aerospace or precision electronics, it costs 5–10x more than FR4, limiting its use to niche applications.

For most designs, 0.3W/mK FR4 remains the best choice, with upgrades justified only when power levels or ambient temperatures exceed its capabilities.

Research is underway to enhance FR4’s thermal conductivity while preserving its cost and processability:

Nano-Filler Integration: Adding graphene or carbon nanotubes (CNTs) to epoxy resins creates conductive pathways for phonons. Lab tests show CNT-reinforced FR4 with 0.4–0.5W/mK conductivity, a 30–60% improvement over standard FR4, with commercialization expected in the next 3–5 years.

3D Woven Glass Fibers: Advanced weaving techniques create more continuous glass networks in the epoxy matrix, reducing thermal barriers. Prototypes with 3D-woven E-glass achieve 0.35–0.4W/mK, with potential for further gains as weaving technology improves.

Bio-Based Epoxies: Derived from plant oils, these resins offer similar thermal conductivity to traditional epoxy (~0.15W/mK) but with lower environmental impact. When combined with ceramic fillers, they could match the performance of thermally enhanced FR4 while reducing carbon footprints.

FR4 PCB’s thermal conductivity of 0.3W/mK is a defining characteristic that balances practicality and performance for the majority of electronic applications. Far from a limitation, this value reflects FR4’s optimal positioning as a cost-effective, manufacturable material that meets the needs of low-to-moderate power devices. By understanding the material science behind 0.3W/mK and implementing design strategies like thermal vias, thick copper, and strategic component placement, engineers can maximize heat dissipation within this constraint. While alternatives exist for high-power scenarios, 0.3W/mK FR4 remains the workhorse of the electronics industry, with ongoing innovations poised to extend its capabilities even further. For designers, recognizing the strengths of 0.3W/mK FR4—and working within its bounds—remains key to creating reliable, cost-effective electronic systems.

Got project ready to assembly? Contact us: info@apollopcb.com

We're not around but we still want to hear from you! Leave us a note:

Leave Message to APOLLOPCB